The Green Light of Another Language

How an Austrian Poet Might Have Influenced a Great American Novel

Who has twisted us around like this, so that

no matter what we do, we are in the posture

of someone going away? Just as, upon

the farthest hill, which shows him his whole valley

one last time, he turns, stops, lingers—,

so we live here, forever taking leave.

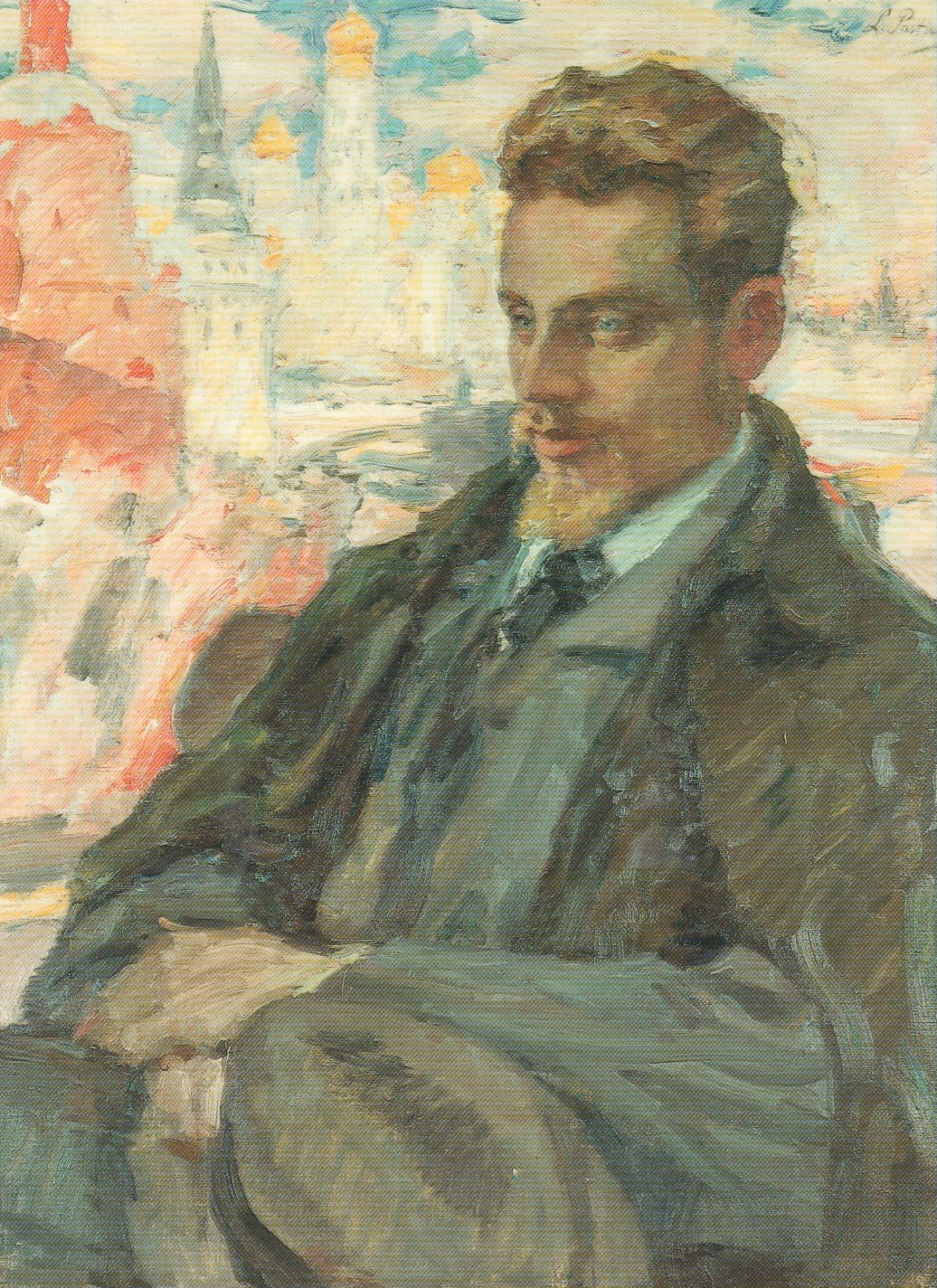

There’s a good chance you’ve never seen these lines before. They’re from a collection of poems called the Duino Elegies, originally published in German in 1923. Unlike most poems, they have a dramatic origin story. Here is their author’s host, Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis-Hohenlohe, recalling what happened that morning in 1912:

Rilke later told me how these Elegies arose. He had felt no premonition of what was being prepared deep inside him; though there may be a hint of it in a letter he wrote: “The nightingale is approaching—” Had he perhaps felt what was to come? But once again it fell silent. A great sadness came over him; he began to think that this winter too would be without result.

Then, one morning, he received a troublesome business letter. He wanted to take care of it quickly, and had to deal with numbers and other such tedious matters. Outside, a violent north wind was blowing, but the sun shone and the water gleamed with silver. Rilke climbed down to the bastions which, jutting to the east and west, were connected to the foot of the castle by a narrow path along the cliffs, which abruptly drop off, for about two hundred feet, into the sea. Rilke walked back and forth, completely absorbed in the problem of how to answer the letter. Then, all at once, in the midst of his thoughts, he stopped; it seemed that from the raging storm a voice had called to him:“Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’ hierarchies?”

He stood still, listening. “What is that?” he whispered. “What is coming?”

Taking out the notebook that he always carried with him, he wrote down these words, together with a few lines that formed by themselves without his intervention. He knew that the god had spoken.

Very calmly he climbed back up to his room, set his notebook aside, and answered the difficult letter.

By the evening the whole First Elegy had been written.

It would ultimately take Rilke ten years to finish the remaining nine elegies.

In 1925, two years after Rilke published his Duino Elegies, an American writer published a novel to some critical success. Unfortunately, it proved to be a commercial failure, and by the year of the author’s death in 1940 the novel had faded into obscurity. You have heard of this novel. It is now a widely recognized masterpiece, and contains one of the most beautifully written last pages in American literature.

Let’s go through a short biography of this American writer, whom we’ll call F. Then we'll look a biography of Rainer Maria Rilke, followed by a few translations of the final stanza of his Eighth Elegy. My aim is to show that it is possible Rilke inspired the last page of F’s famous novel.

The Story of F

F was born in 1896 in the American Midwest. After his father’s wicker business failed, the family moved east to New York. Educated at two boarding schools, F left for Princeton at 17, where he fell in love with the daughter of a wealthy stock broker. Her father quickly intervened, saying, “Poor boys shouldn't think of marrying rich girls.”

A suicidal F dropped out of Princeton and joined the army as a second lieutenant. It was 1917. Perhaps he learned a bit of German in his courses at Fort Leavenworth, or maybe he learned it when he was transferred to Camp Sheridan near Montgomery, Alabama. But it’s doubtful. Any biography written about him wouldn’t mention any fluency in German, for example. Resolved to achieve his literary ambitions before heading off to France, F wrote a novel in three months and sent it off to a New York publishing house. An editor responded with an encouraging rejection.

Meanwhile, F had met and fallen in love with a woman in Montgomery. We’ll call her Z. She refused to marry him until his financial prospects improved.

Before F was shipped off to Europe, the war ended. He returned home and finished his novel and this time the publisher accepted it. Unexpectedly, the novel sold tens of thousands of copies and F was suddenly famous. With his financial problems solved, Z agreed to marry him. They moved to the center of the world: New York City.

A few years passed, he published another novel, wrote dozens of short stories, wrote and staged a failed play, and nearly fell into debt. It was the roaring twenties, the jazz age, his wife was a flapper, he was a drunk, their relationship was tempestuous. He attended parties in extravagant gilded mansions, bacchanalia filled with Hollywood Moguls, New York Intellectuals, Titans of Industry, Famous Comedians, and Gangsters. In 1923, the couple moved to a small cottage on Long Island where F began work on a novel he hoped would be his masterpiece: something beautiful and elegant and intricately patterned. He’d already thrown out, or planned to throw out, his current draft. He had a rare gift for writing beautiful sentences. But what he’d written so far fell short of the novel he’d envisioned. So he threw out the draft and began again.

Slain by a Rose

Some years earlier, in 1912, a young Austrian poet spent a few months at the castle of a wealthy patroness. There he had one of the major insights of his life, and in a creative whirlwind rare in the history of literature conceived of a series of poems that would take him ten years to complete. War and depression and the vicissitudes of poetic creation interrupted his dream, but in 1922 he finished his collection. They are named after the castle where he had his first inspiration. They wouldn’t be translated into English until 1931.

One story of his death in 1926 goes like this:

To honour a visitor, the Egyptian beauty Nimet Eloui Bey, Rilke gathered some roses from his garden. While doing so, he pricked his hand on a thorn. This small wound failed to heal, grew rapidly worse, soon his entire arm was swollen, and his other arm became affected as well, and so he died.

A poet slain by a rose! This must be one of the most poetically apt deaths in history. If only it were true. He actually died of leukemia.

The French Riviera

In 1924, two years before Rilke’s death, F and his wife Z took a booze-free ship to Europe, where they joined a group of American expatriates in France, before continuing on to the French Riviera. There they rented a villa so F could work on his novel. One night while attending a party at a wealthy couple’s villa, F walked into their library and came across a recently published book by an Austrian poet. It wouldn’t be translated into English for seven more years, but the hostess was fluent in German, had spent some years as a teenager living in Berlin with her family. At F’s request she translated a few of the poems. She had a gift for translation, both she and her husband were artists with a fine taste for everything. They were a rare social nexus: a wealthy couple who collected both art and artists. Famous painters, musicians, writers were often at their villa.

While F’s hero was Joseph Conrad, and the guiding light to his current book the preface to Conrad’s Narcissus, he discovered a new love for this Austrian poet’s lyric poetry. So he borrowed their copy of the poet’s masterpiece and a friend’s German-English dictionary from 1906.

Years later F would write about how he could never remember the periods of his life when he was working on a novel. He lived in the story, he said. Perhaps he was simply too busy, too immersed, to translate the Austrian poet. So Z, who likely didn’t speak German either, began translating it for him.

It had been months since they moved to the French Riviera. Months of writing and rewriting. As F prepared to send the complete manuscript to his editor in New York City, he decided to take the final paragraphs of his first chapter and place them on the last page of his novel. But they didn’t quite work as an ending, so that night he planned to add a few more lines.

Meanwhile Z had just finished translating the last six lines of Rilke’s Eighth Elegy.

The Eighth Elegy

This is what she saw:

Wer hat uns also umgedreht, daß wir,

was wir auch tun, in jener Haltung sind

von einem, welcher fortgeht? Wie er auf

dem letzten Hügel, der ihm ganz sein Tal

noch einmal zeigt, sich wendet, anhält, weilt—,

so leben wir und nehmen immer Abschied.

Here are two translations by professional translators.

Then who has wheeled us backwards, so that we,

no matter the action, always seem to have

the stance of those about to depart? Like someone

on the final hill, which one more time shows him

his entire valley, who turns, pauses, lingers—,

and so we live, constantly saying farewell.

Who has twisted us around like this, so that

no matter what we do, we are in the posture

of someone going away? Just as, upon

the farthest hill, which shows him his whole valley

one last time, he turns, stops, lingers—,

so we live here, forever taking leave.

Translated by Stephen Mitchell (you’ve seen this before)

What is this saying? We’ll have to go back to the start of the Eighth Elegy. The elegy explores the difference between the way animals and humans experience reality. It says we human beings alone exist in a world of objects. We alone know we will die. Our gift for language has done this to us. We transform things into words and call those words objects. The poet laments what we have lost by orienting ourselves in this way: the freedom to exist in all time. Children understand that freedom—it is their natural birthright—but lose it as they are forced to pay attention to the human world of objects, culture, ideas. We only return to it when we are near death or in love. But by the nature of love we are almost immediately blocked by the object of our love, and so the vision of the animal world of wordless consciousness fades. Part of the tragic nature of our gift is that even as we move forward in time, we are always looking back, because we can see who we used to be, the freedom we used to have. Rilke calls this freedom the Open, or that “pure unseparated element which one breathes without desire and endlessly knows.”

The Great Gatsby

Now let’s return to F. He’s trying to write the final lines of his novel. He’s having some difficulty, and has just glanced at Z’s partial translation of the Duino Elegies. We’ll expand F’s name to F. Scott Fitzgerald, and his wife Z to Zelda Fitzgerald. And the novel he was working on we’ll call The Great Gatsby (though he hasn’t quite settled on that title). What makes this novel so lovely is that it is near perfect. It is short and well-plotted and beautifully written. Its central themes are of lost love, of focusing too much on a dream at the expense of the present, of the excesses of the roaring twenties, and the poisoned heart of the American Dream, which whispers that you too can have what they have. A man deeply in love with a woman from his past imagines she will be his future as well. But he is also partly like one of Rilke’s animals, for he cannot see his death, cannot even believe in it. He has no sense of what he has already lost. If he did, he wouldn’t be there in that mansion, trying to lure Daisy back into his life by throwing party after party, hoping she’ll wander in one day, and fall back in love with him.

It is possible Zelda never translated the Eighth Elegy for F. Scott Fitzgerald. Maybe neither of them could have. But someone at one of those parties had read the Duino Elegies. Even if Gerald or Sara Murphy hadn’t yet read his Elegies, Rilke was too famous, too well known, and their circle too educated, too artistic, not to be familiar with Rilke, and aware of his recently published masterpiece. I don’t know who it was who first introduced the Duino Elegies to Fitzgerald, but I imagine it went something like this: Someone shows up at one of these parties with a copy and begins reciting it in German, maybe some drunken monolingual Irish-American whose last name rhymes with Schmitzgerald complains, so they translate it as they read into English, perhaps someone fluent in German joyfully offers a few corrections, and the whole Elegies, or even a piece, are recited, explained, talked over.

And so even if Fitzgerald (or Zelda) never translated it, the themes and language of the Duino Elegies were in the air that year. It wouldn’t be surprising for a novelist in his late twenties to be influenced by them. Even if he wasn’t aware of it.

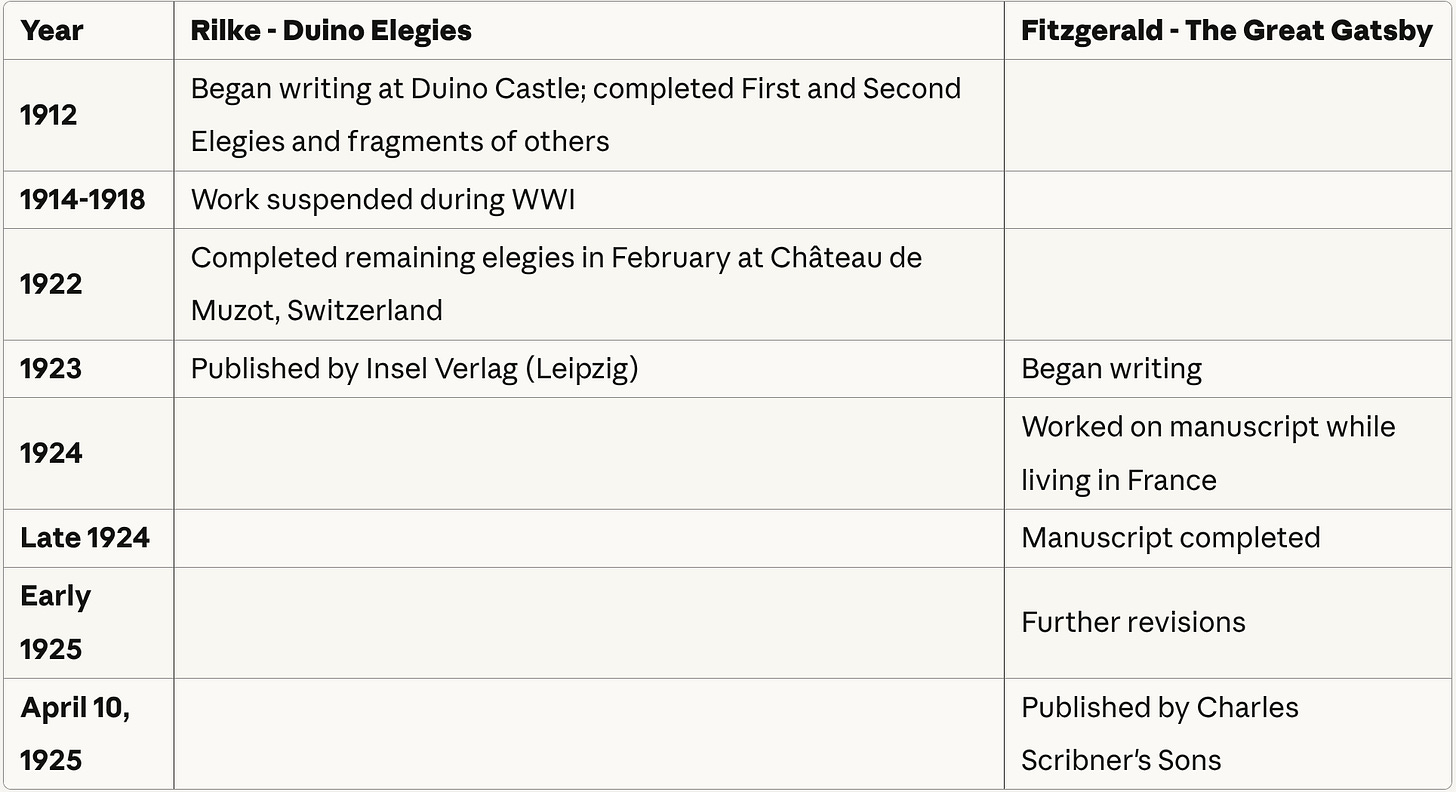

Timeline

In truth, I can’t prove Fitzgerald read Rilke’s Eighth Elegy. None of his letters mention it, he never even owned a copy of Rilke’s poetry. But I can prove it was possible, even likely, for him to have heard of Rilke. And I can try and show how Rilke’s influence shaped Fitzgerald’s work, whether he was conscious of it or not.

The Fitzgeralds attended parties hosted by Gerald and Sara Murphy. The Murphy’s knew Igor Stravinsky. And Stravinsky had the same patron as Rilke.

I want to share a timeline so that you can see, side by side, when Rilke was working on his Duino Elegies, when it was finally published, and when Fitzgerald was working on The Great Gatsby, and when his drafts were finished and the novel published. And then finally at the end we’re going to look at the last page of The Great Gatsby, which we already know is one of the most famous last pages in the history of American literature. Rilke is at least as beloved as Fitzgerald. If you’ve ever read his Letters to a Young Poet, you know what I mean. If you haven’t, please stop reading this immediately and go read them. And afterwards, if you’d like, return here. If you never return, that’s okay. I’m delighted to have directed you in his direction. Rilke also has these impossibly gorgeous poems, which you should absolutely read. Any writer who has a beautiful mind will reveal themselves to you within a few lines. Fitzgerald is like that and Rilke is like that.

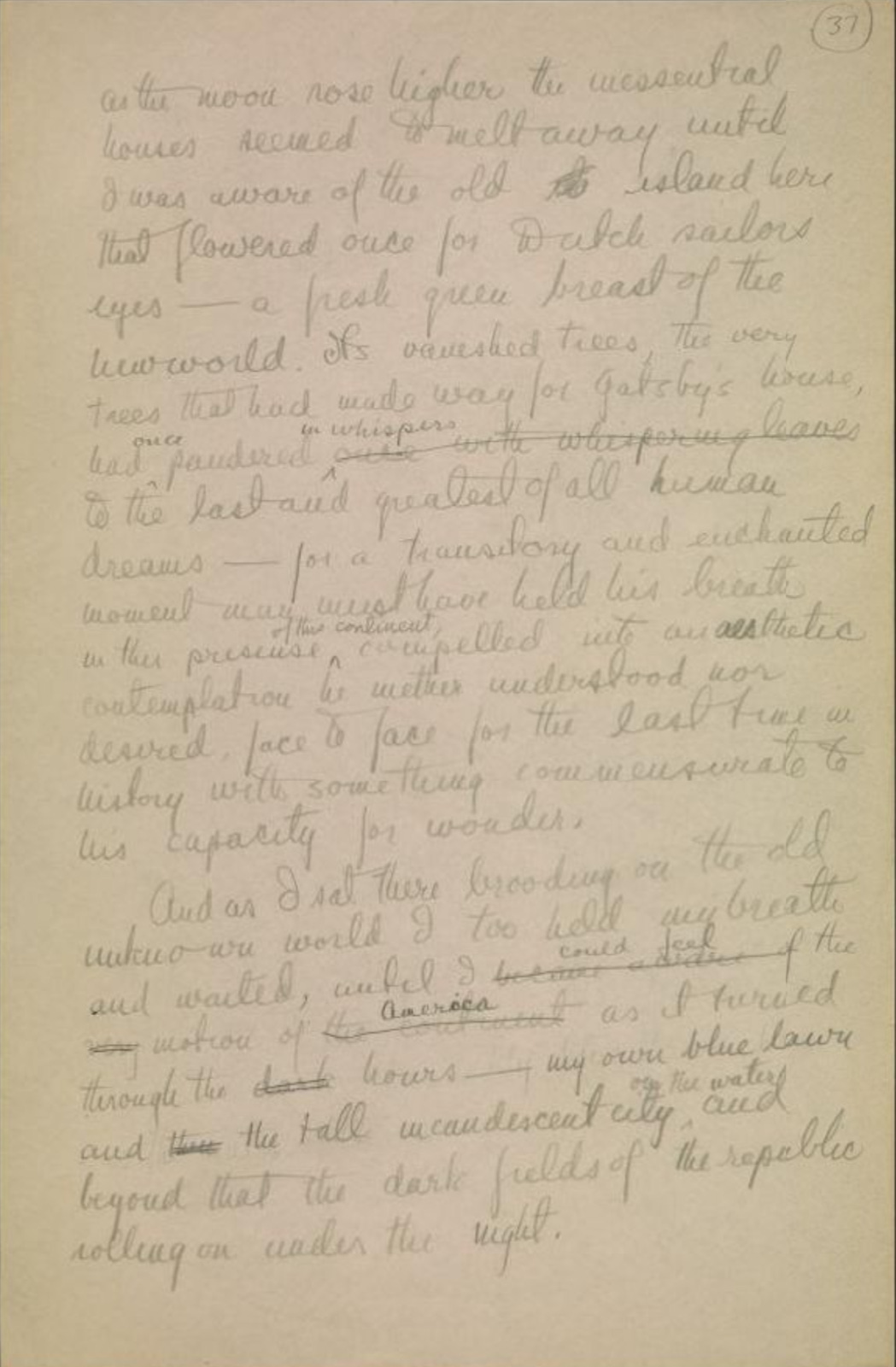

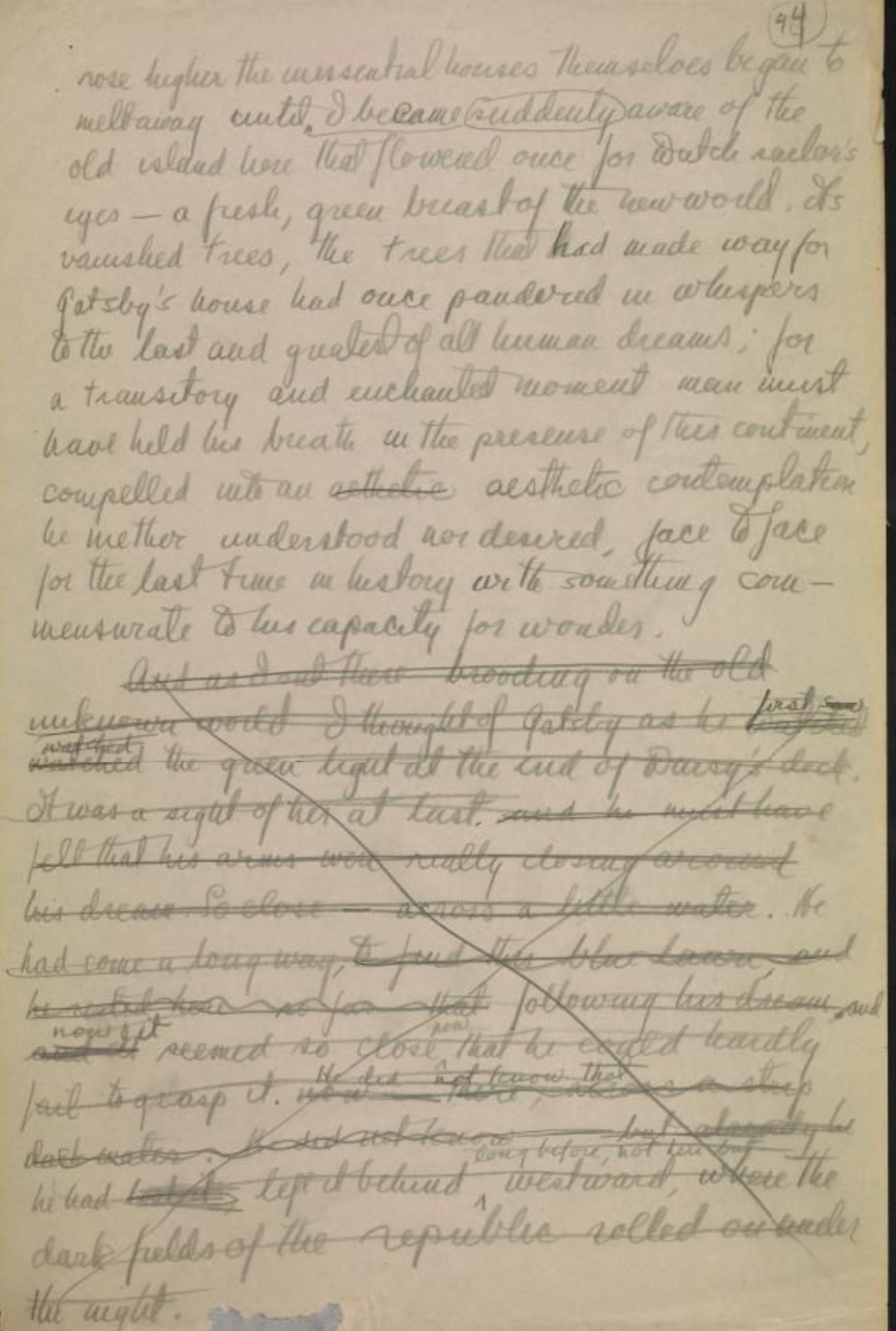

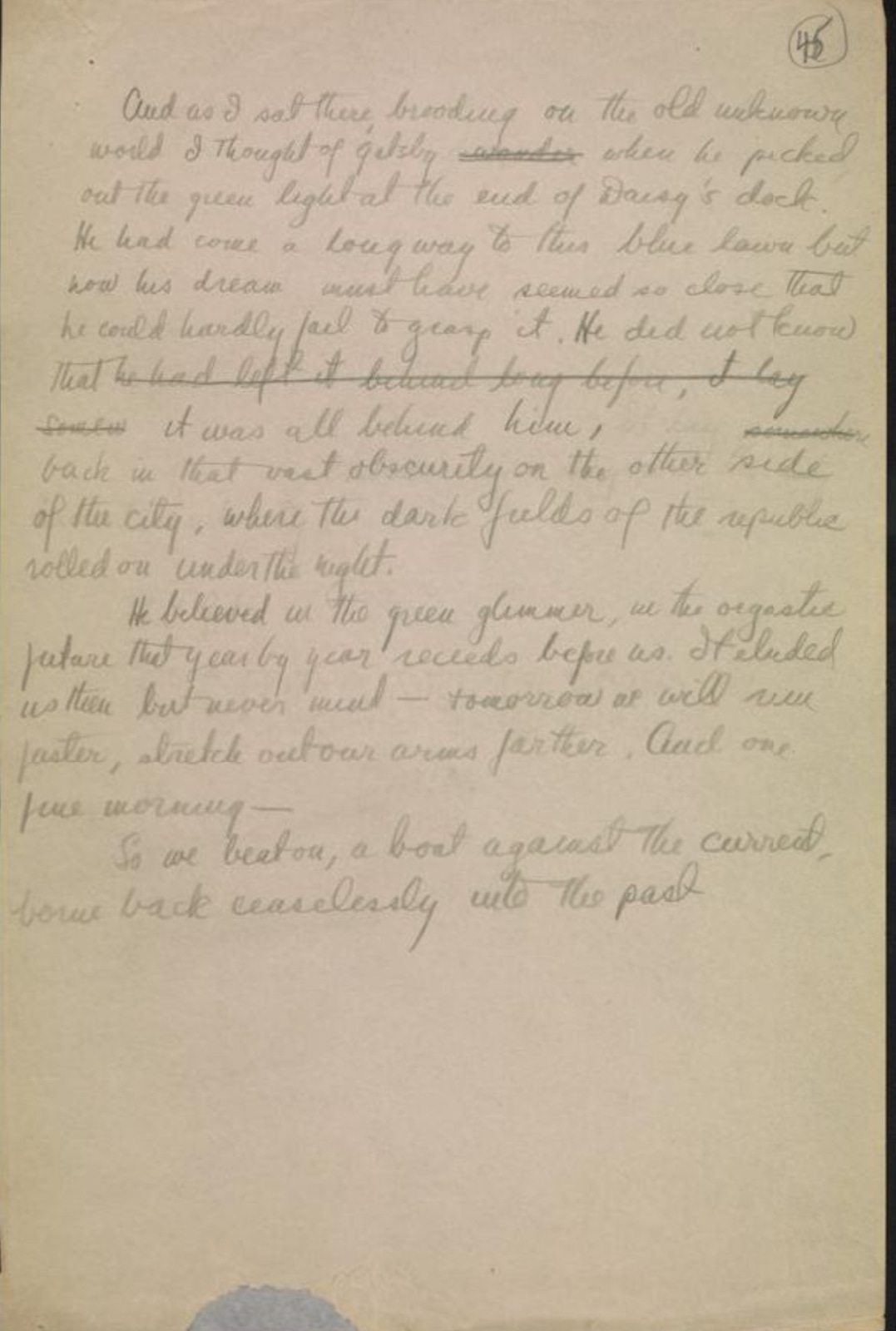

Princeton has the Autograph Manuscript, Galley, and First Edition of The Great Gatsby available on their website. I wanted to find the earliest draft containing the true last lines of his novel.

Remarkably, the final page of the book was originally at the end of the first chapter.

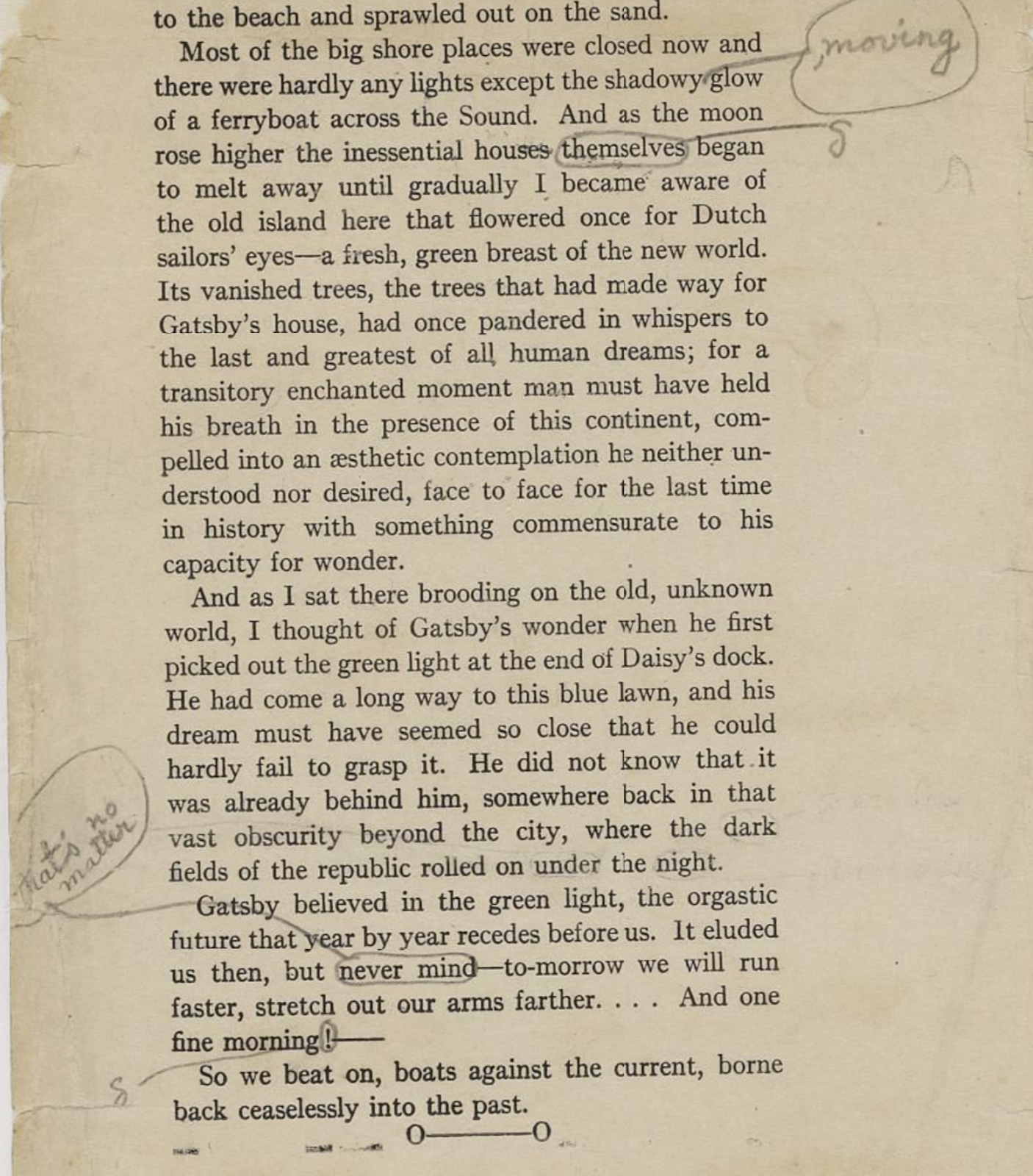

He later moved those paragraphs to the end of the book and added a few lines. Here are the final two pages of the Autograph Manuscript.

And below is the final page from his galley—the final version before the manuscript goes to press.

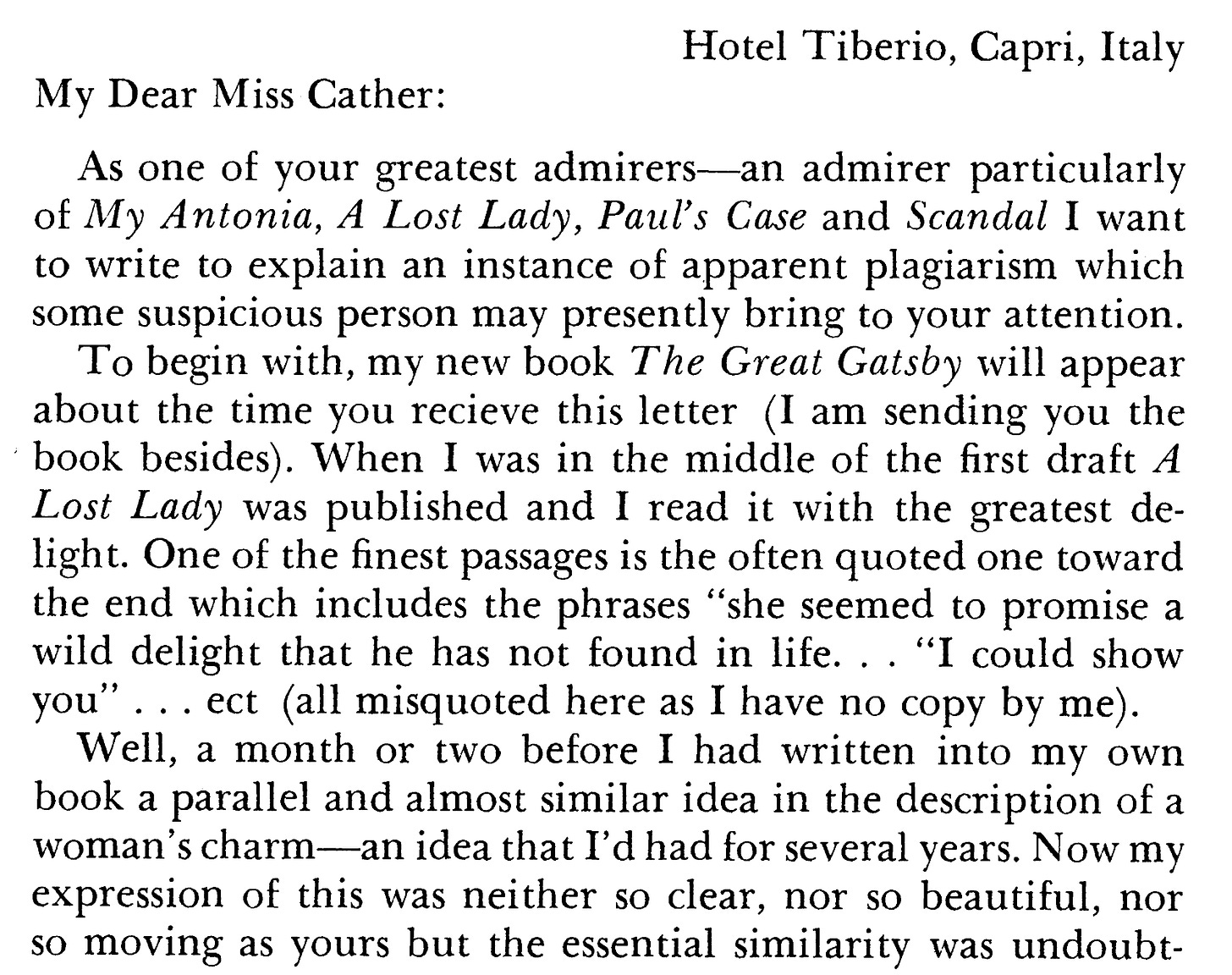

Cryptomnesia

Before we go any further I want to ask the following question. Has F. Scott Fitzgerald shown a pattern of cryptomnesia (inspiration not quite approaching plagiarism) in his writing? I won’t be exhaustive here. One example1 is enough2:

It's interesting isn't it, how he can recognize similarities in prose between his own writing and another author's. His friends, even Willa Cather herself, ultimately convinced him that he hadn’t plagiarized her passage. I don't think he did either. I think he was influenced by her, and it is exactly as he said, that an idea already flowering in his mind found its expression not through her language but through the feeling behind it. At worst, it is another example of cryptomnesia. While not quite reaching the bar of plagiarism, it does show that Fitzgerald was aware of overt similarities between his work and others.

So We Live, So We Beat On

Suppose you didn’t know English or German, had in fact never encountered any Romantic/Germanic, or Indo-European language in your life. I wanted to try an experiment, so I asked a large language model to create a new language derived from Proto-Indo-European.

In our new language the last two lines of The Great Gatsby might look something like:

ᛟᚢᛏ ᛟᚢᚱ ᚨᚱᛗᛊ ᚠᚨᚱᚦᛖᚱ. . . . ᚨᚾᛞ ᛟᚾᛖ ᚠᛁᚾᛖ ᛗᛟᚱᚾᛁᚾᚷ——

ᛊᛟ ᚹᛖ ᛒᛖᚨᛏ ᛟᚾ, ᛒᛟᚨᛏᛊ ᚨᚷᚨᛁᚾᛊᛏ ᚦᛖ ᚲᚢᚱᚱᛖᚾᛏ, ᛒᛟᚱᚾᛖ ᛒᚨᚲᚲ ᚲᛖᚨᛊᛖᛚᛖᛊᛚᚣ ᛁᚾᛏᛟ ᚦᛖ ᛈᚨᛊᛏ.

And the last two lines of Rilke’s Eighth Elegy:

ᚾᛟᚲᚺ ᛖᛁᚾᛗᚨᛚ ᛗᚨᛚ ᛗᚨᛚ ᛗᚨᛁᛚ ᛊᛁᚲᚻ ᚹᛖᚾᛞᛖᛏ, ᚨᚾᚺᛖᛚᛏ, ᚹᛖᛁᛚᛏ—,

ᛊᛟ ᛚᛖᛒᛖᚾ ᚹᛁᚱ ᚢᚾᛞ ᚾᛖᚺᛗᛖᚾ ᛁᛗᛗᛖᚱ ᚨᛒᛊᚲᚺᛁᛞ.

The first time I looked at them together, I thought they looked similar. It was the M dash, and Fitzgerald’s double M dash, which each precede their final lines, that drew my attention. But it was their meaning that held it. The So we live of Rilke versus the So we beat on of Fitzgerald. The forever taking leave of Rilke versus the borne back ceaselessly into the past of Fitzgerald. The meaning of their final lines are too similar, their publication in time too close.

Take a look at a few translations of Rilke’s last line versus Fitzgerald’s:

Rilke: so leben wir und nehmen immer Abschied.

Rilke: That’s how we’ve lived, forever parting.

Rilke: So we live and take eternal leave.

Rilke: So we live, and are always taking leave.

Rilke: So do we live, and ever bid farewell.

Rilke: And so we live, constantly saying farewell.

Rilke: So we live here, forever taking leave.

Fitzgerald: So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

In Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, we have a man reaching out to the future, forever pulled back into the past.

And at the end of Rilke’s Eighth Elegy we have someone moving toward the future, forever looking backward.

1924

I wanted to see what it would look like if I tried to translate Rilke myself. I imagined I was a writer living in the French Riviera in 1924, with access only to the resources of the time. I bought a 1906 German-English dictionary and translated the final stanza of the Eighth Elegy, and then used a 1913 Webster’s Unabridged dictionary to refine my translation. The result is fairly crude, but even with my complete lack of German, it wasn’t difficult to translate the meaning of his final stanza.

Who has turned us around so, that we

whatever we do, in that holding

from one, which goes away? How he by

this final hill, shows him his valley

one last time, turns around, stops, lingers—,

So we live, taking ceaseless departure.3

I'm not happy about ‘final hill’ or ‘taking ceaseless departure,’ and the grammar is atrocious, but I figure it's not too bad for a few hours of flipping through dictionaries. The goal was to translate the meaning of the final stanza to see what it would look like if either of the Fitzgeralds translated it themselves. And I can see the meaning clearly here: of a person constantly moving forward in time while looking back into the past.

Let’s return to Rilke’s Eighth Elegy. Remove the final two lines, and look at how they compare to the end of The Great Gatsby (with a few lines removed) in the following professional translations:

Rilke

Who has twisted us around like this, so that

No matter what we do, we are in the posture

Of someone going away? Just as, upon

The farthest hill, which shows him his whole valley

Fitzgerald

And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder…

He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

They are so similar! I feel Rilke’s influence within Fitzgerald’s prose. Even if he never read him, it’s there for me.

Take a look, one last time, at the final stanza of the Eighth Elegy, and compare it to one of the most beautiful last pages in all American literature.

Rilke

Who has twisted us around like this, so that

no matter what we do, we are in the posture

of someone going away? Just as, upon

the farthest hill, which shows him his whole valley

one last time, he turns, stops, lingers—,

so we live here, forever taking leave.

Fitzgerald

Most of the big shore places were closed now and there were hardly any lights except the shadowy, moving glow of a ferryboat across the Sound. And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes—a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter— tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . . And one fine morning——

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

End

It is possible both Rilke and Fitzgerald were influenced by the same author, and that that is the source of their similar lines. Maybe they came at their lines independently. I don’t know. The question I have been asking myself is: Was it possible for F. Scott Fitzgerald to have been influenced by the last few lines of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Eighth Elegy while writing the final lines of The Great Gatsby?

The answer is: Yes, it’s possible.

I know what it means to be influenced. I modeled my novel, The Ogre, off of John Banville’s The Sea. I'd been writing short fiction for seven years when my younger brother unexpectedly passed away. I was in shock for three months. When the numbness abated I discovered I could write with complete emotion every third day. So I set out to write a novel with a structure that could contain both the numbness and overflowing emotion of grief in beautiful prose, and I hadn't seen anyone do it so well in the past few decades as in The Sea. So I deformed his structure into a new shape, and wrote my story within those boundaries. Banville is one of my influences, and I can name over two dozen others.

Here are some of Fitzgerald’s influences:

Fitzgerald’s reading, though fairly wide, was quite selective. He picked the periods, the artists, and the genres that were necessary to his own particular genius—the lyric poetry of the English Renaissance (Shakespeare), the early nineteenth century (romantic poets, especially Keats), the late nineteenth century (French symbolists, Browning, Swinburne, Kipling), the twentieth century (Brooke, Eliot); the novel of social realism (Thackeray, Butler, Norris, Dreiser, Proust, Wharton); the “novel of selection” (Flaubert, James, Joyce, Conrad, Cather, Hemingway).

The ugly truth is that books come from books, says a cowboy. Every writer is influenced by the past. Whether through the anxiety of influence, cryptomnesia, commonplace plagiarism, structural or thematic inspiration, books come from other books.

I want to add Rilke to the list.

At its simplest, those last lines from the poet and the novelist reduce themselves to:

Rilke

Man on a hill

Looking back

Forever taking leave of the past

Fitzgerald

Man in a boat

Leaning forward

Forever pulled back into the past

There are times when I want to go even further than the Eighth Elegy. Not only do I think that Fitzgerald took from the end of the Eighth Elegy. I think he was also influenced by the Duino Elegies in general, and this thematically deepened The Great Gatsby. Rilke’s elegies seek to know why we use poetic language. What purpose does it serve? His answer lies in the ninth elegy. The traveler at the end of the eighth elegy standing on the hilltop forever looking back, now in the ninth elegy descends into the valley, and brings with him a word. That is all we are here for, the ninth elegy says. To take things (a flower, a leaf, a cloud) and transform them into words so that even when the thing itself vanishes the word might remain. Perhaps, suggests the elegy, the Earth gave itself language so that it too might transform into words.

That is precisely the task the narrator of The Great Gatsby, and by extension the author, has set for himself. To transform the thing (Gatsby, and the events of that summer) into an enduring object: the novel.

There is more to say, but this has gone on too long, and I am content to stop here, for now. It’s been enough in this post to prove the possibility of Rilke’s influence on Fitzgerald.

But I can’t help one final remark.

If Fitzgerald used Rilke’s Eighth Elegy to craft the final page of The Great Gatsby, that does not make the novel any less beautiful. To believe that a man with a mind for gorgeous language saw the same poetic genius in another and took from it what he could, consciously or not, only deepens the beauty of both writers.

‘Daisy’s remark, “I hope it’s beautiful and a fool—a beautiful little fool”, is partly attributable to Zelda, although Scott himself added the additional observation, “That’s the best thing a girl can be in this world”. After the birth of his daughter Scottie in October 1921, in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Fitzgerald heard his anesthetized wife murmur: “Oh God, goofo [sic] I’m drunk. Mark Twain. Isn’t she smart—she has the hiccups. I hope it’s beautiful and a fool—a beautiful little fool.”’

Fitzgerald’s likely inspiration for some of the paragraphs in the final chapter of The Great Gatsby.

(The Great Gatsby, penultimate lines)

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgasmic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . . And one fine morning——”

(Youth: A Narrative by Joseph Conrad)

“And we all nodded at him: the man of finance, the man of accounts, the man of law, we all nodded at him over the polished table that like a still sheet of brown water reflected our faces, lined, wrinkled; our faces marked by toil, by deceptions, by success, by love; our weary eyes looking still, looking always, looking anxiously for something out of life, that while it is expected is already gone—has passed unseen, in a sigh, in a flash—together with the youth, with the strength, with the romance of illusions.”

(The Great Gatsby, final chapter)

“That’s my Middle West—not the wheat or the prairies or the lost Swede towns, but the thrilling returning trains of my youth, and the street lamps and sleigh bells in the frosty dark and the shadow of holly wreaths thrown by lighted windows on the snow. I am part of that, a little solemn with the feel of those long winters…. I see now that this has been a story of the West after all…”

Versus

(Youth: A Narrative, near the end)

“And this is how I see the East. I have seen its secret places and have looked into its very soul; but now I see it always from a small boat, a high outline of mountains, blue and afar in the morning; like a faint mist at noon; a jagged wall of purple at sunset. I have the feel of the oar in my hand, the vision of a scorching blue sea in my eyes. And I see a bay, a wide bay, smooth as glass and polished like ice, shimmering in the dark. A red light burns far off upon the gloom of the land, and the night is soft and warm. We drag at the oars with aching arms, and suddenly a puff of wind, a puff faint and tepid and laden with strange odours of blossoms, of aromatic wood, comes out of the still night—the first sigh of the East on my face. That I can never forget. It was impalpable and enslaving, like a charm, like a whispered promise of mysterious delight.

(Youth: A Narrative, near the end)

“And then I saw the men of the East—they were looking at me. The length of the jetty was full of people. I saw brown, bronze, yellow faces, the black eyes, the glitter, the colour of an Eastern crowd. And all these beings stared without a murmur, without a sigh, without a movement. They stared down at the boats, at the sleeping men who at night had come to them from the sea. Nothing moved. The fronds of palms stood still against the sky. Not a branch stirred along the shore, and the brown roofs of hidden houses peeped through the green foliage, through the big leaves that hung shining and still like leaves forged of heavy metal. This was the East of the ancient navigators, so old, so mysterious, resplendent and sombre, living and unchanged, full of danger and promise.”

Appendix: German-English Dictionary Entries Used

Abschied - discharge, dismissal, departure, leave, adieu, good-bye, farewell, parting, certificate, recess (law). Abschied nehmen - to bid farewell, to take leave

Als - than, as, as in the capacity or character of,

Auch - also, too, even, likewise, (after wir = ever, soever)

Auf - on, upon, in, of, at, by

Das - the, which or that

Der - that, this, he, it, who

Einem - a, an

Einmal - once, one time

Er - he, you

Fortgehen - to go away, go forth, to go on or forward, to progress, to continue

Ganz - whole, entire, all, complete, excellent

Haltung - holding, keeping, maintenance, support, prop, deportment, carriage, mien, fulfilling, delivery (of speeches), session, holding of a session, harmony (of color, etc.)

Hat (haben) - to have, to possess, to hold (a feeling),

Hügel - hill

Ihm - to him, to it, to you

Immer - perpetually, continually, always, ever, every time, more and more, nevertheless, yet, still

In - preposition expressing rest or (limited or circular) motion in a place; implying motion to or towards, in, at, into, to, within

Jener - yon, that, yonder; on the other side of the river

Letzen - leave-taking, farewell, parting-gift

Leben - to live, be alive, to pass one’s life, to dwell, to feed

Nehmen - to take, to seize, lay hold of, to receive

Noch - still, yet, else

Sein - to be

Sich - itself

Sind - you (from sein - to be)

Tal - valley, dale

Tum - turn round, to stir about, to give exercise to, to keep, to wheel (a horse around)

Umgeh - to go round; to revolve; to circulate; to change, shift (of wind)

Uns - us, to us, ourselves, to haunt, to walk in one’s sleep

Von - of, from

Von Einem - from one, from a

Wer - who

Wir - we

Was - what or why

Welch - which

Wend - turn, turning, turning-point, change, beginning of new epoch

Weilt - stay, stop, tarry, linger, sojourn

Wie - how, in what way, in what degree

Zeigt - shows

Was wir auch tun - whatever we do, no matter what we do, even if we do